Origins and Creation (1930-1931)

Betty Boop first appeared in the animated short Dizzy Dishes on August 9, 1930, produced by Max Fleischer’s Fleischer Studios. Initially, she was a supporting character—a canine flapper with long ears, voiced by Mae Questel.

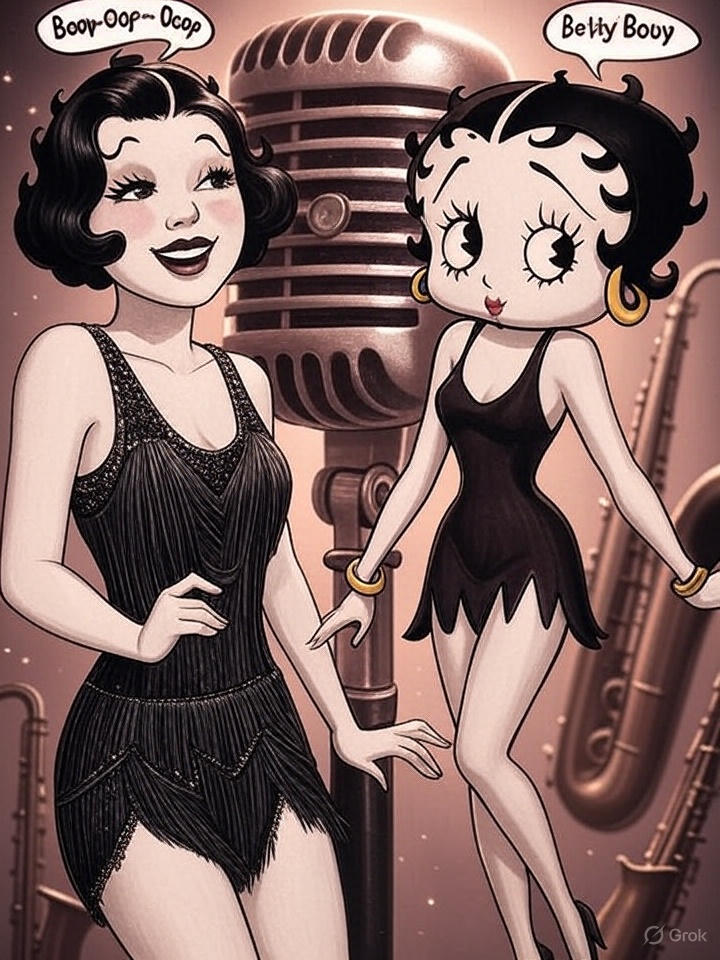

Her design drew from 1920s jazz culture and flapper aesthetics, with influences from performers like Helen Kane, known for her “Boop-Oop-a-Doop” scat style. However, historical claims (e.g., by Esther Jones’ advocates) suggest her scat-singing may trace back to Jones’ 1920s performances in Harlem and Paris, which Kane mimicked.

By 1931’s Betty Co-ed, she became human, shedding her dog features, with a curvier figure, short black dress, and signature garter. This shift reflected Hollywood’s growing influence on animation.

The film Too Cute for Words can depict this transition as a nod to Esther’s erased legacy, with Betty’s 1931 humanization paralleling the conspiracy to overshadow Jones’ contributions.

Golden Age and Peak Popularity (1932-1934)

Betty starred in over 90 cartoons, with classics like Minnie the Moocher (1932) featuring Cab Calloway, showcasing her jazz roots. Her voice and movements embodied the Depression-era escapist fantasy.

Her look solidified with a red dress, hoop earrings, and exaggerated features (large eyes, small nose), blending 1930s glamour with cartoon exaggeration. The “Boop-Oop-a-Doop” catchphrase became her trademark.In 1934, the

Motion Picture Production Code (Hays Code) imposed stricter morality standards, toning down her sexuality. Shorts like Betty Boop’s Rise to Fame shifted to family-friendly plots, reducing her provocative edge.

In 1934, the Motion Picture Production Code (Hays Code) imposed stricter morality standards, toning down her sexuality. Shorts like Betty Boop’s Rise to Fame shifted to family-friendly plots, reducing her provocative edge.

The 1932-1934 peak aligns with Esther’s potential influence, offering a timeline for the conspiracy’s impact (Too Cute for Words). The Hays Code shift can symbolize the sanitization of her Black roots, a key plot point.

Decline and Revival (1935-1980s)

Post-1934, Betty’s shorts declined in number and boldness, with her last major release, Rhythm on the Reservation (1937), marking the end of her starring role. Fleischer Studios shifted focus to Superman and Popeye.

Paramount sold the rights in 1941, and Betty faded until TV syndication in the 1950s revived interest. Her image appeared in merchandise but lacked new content.

The decline can frame the modern-day rediscovery by Marie Mountview (Too Cute for Words) highlighting how Esther’s story was buried alongside Betty’s original intent.

Modern Revival and Legacy (1980s-Present)

The 1980s saw a Betty Boop resurgence, with King Features Syndicate licensing her image for merchandise (clothing, dolls) generating $1B+ globally. Films like Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988) nodded to her, and a 1993 TV special attempted a reboot.

Betty became a feminist icon and pop culture staple, with debates over her appropriation of Black jazz culture (e.g., Esther Jones’ influence) gaining traction in the 2020s, especially on X (e.g., #EstherJones trending in 2021).

The 2025 in the Too Cute for Words setting allows Marie to uncover this history, tying Betty’s revival to Esther’s legacy. Merchandise potential (e.g., Esther-Betty dolls) aligns with the film’s $50M+ ancillary goal.

Stylistic and Thematic Elements

Early black-and-white rotoscoping (tracing live-action) gave way to color in the 1930s, with bold outlines and exaggerated movements. This influenced her playful, flirty persona.

Escapism, female empowerment, and jazz rhythm dominated her early shorts, later shifting to domesticity under censorship.

Her scat-singing and dance moves echo Jones’ 1920s performances, suggesting a direct lineage the film can explore through flashbacks and Betty’s cameo.

Historical Controversies

In 1932, Kane sued Fleischer Studios, claiming Betty copied her style. The case highlighted scat-singing’s origins, with evidence of Esther Jones’ earlier use emerging later (e.g., 1934 Gertrude Saunders’ testimony). The suit was dismissed, but it fueled debates.

Modern scholars (e.g., 2020s X posts) argue Betty’s creation erased Black contributors like Jones, a central theme for the film’s conspiracy narrative.

Application to the Film Too Cute for Words

Narrative Integration:

1920s Flashbacks: Show Esther’s scat-singing and Charleston influencing Kane, leading to Betty’s 1930 debut.

1920s Flashbacks: Show Esther’s scat-singing and Charleston influencing Kane, leading to Betty’s 1930 debut.

1930s Transition: Depict Betty’s humanization (1931) as the conspiracy’s peak, with Esther’s disappearance aligning with Kane’s lawsuit.

2025 Resolution: Marie’s discovery ties Betty’s revival to Esther, using 1930s footage as evidence.

Costume Design:

Early Betty: Canine flapper with long ears, transitioning to the 1930s red bias-cut dress with gloves (per 1930s trends).

Esther’s Influence: Gold satin bias-cut dress for her final performance, mirroring Betty’s elegance.

Visuals: Use charcoal sketches with black-and-white rotoscope effects for 1930s scenes, shifting to color for the 2025 festival.

Conclusion

Betty Boop’s cartoon history—from her 1930 jazz-inspired debut to her 1980s revival—offers a rich tapestry for “Boop-Oop-a-Doop”. Her evolution mirrors Esther’s erased legacy, providing a compelling arc for the film’s conspiracy and redemption themes. The 1930s stylistic shift and cultural debates enhance authenticity and relevance, supporting the $40M investment’s cultural and commercial potential.