The Boop-Oop-a-Doop Mystery: Unraveling the True Star Behind Betty Boop’s Catchy Tune

Picture this: a smoky 1920s jazz club, the air buzzing with syncopated rhythms and a singer belting out a playful “Boop-Oop-a-Doop!” that makes the crowd go wild. That’s not Betty Boop, the cartoon queen we all know, nor is it Helen Kane, the flapper who claimed the phrase. No, the real star of this story is Esther Jones—aka Baby Esther—a pint-sized powerhouse who set the stage for one of pop culture’s most iconic catchphrases.

Buckle up, because we’re diving into a tale of jazz, theft, and a long-overdue spotlight on a forgotten legend!

Scat’s Where It’s At: The Roots of “Boop-Oop-a-Doop”

Long before Betty Boop batted her cartoon lashes, scat singing was the hottest thing in jazz. This improvisational art form—think vocal acrobatics with nonsense syllables like “ba-da-bee” or “zippity-zow”—was born in the vibrant Black music scene of the early 20th century. Trailblazers like Edith Griffith, Mae Barnes, Florence Mills, and Gertrude Saunders were riffing with scat, turning simple syllables into musical magic.

Gertrude Saunders, a fierce rival of blues icon Bessie Smith, claimed she pioneered scat as early as 1921 in the all-Black Broadway hit Shuffle Along. In 1934, she didn’t mince words, calling out Helen Kane and the Betty Boop creators for swiping her style. “I did it first!” she declared, and she wasn’t wrong. But while Saunders laid the groundwork, another star was about to steal the show—and the phrase that would echo through history.

Enter Baby Esther: The Tiny Titan of Jazz

Cue the spotlight on Esther Jones, better known as Baby Esther, a child prodigy who could light up a stage like nobody’s business. Born around 1919, this pint-sized performer was barely out of pigtails when she started wowing audiences with her sassy dance moves and scat-singing flair.

By the late 1920s, she was a sensation, not just in the U.S. but across Europe—Paris, Stockholm, Berlin, Madrid—and even in Brazil and South America. Crowds couldn’t get enough of her infectious energy and that signature “Boop-Oop-a-Doop” she tossed into her songs like a musical cherry on top.

In 1928, a grainy sound film captured Esther belting out her scat-tastic phrase, a piece of evidence that would later blow the lid off the Betty Boop origin story. Esther wasn’t just a performer; she was a pioneer, and her voice was about to inspire one of the most famous cartoons ever—whether she got the credit or not.

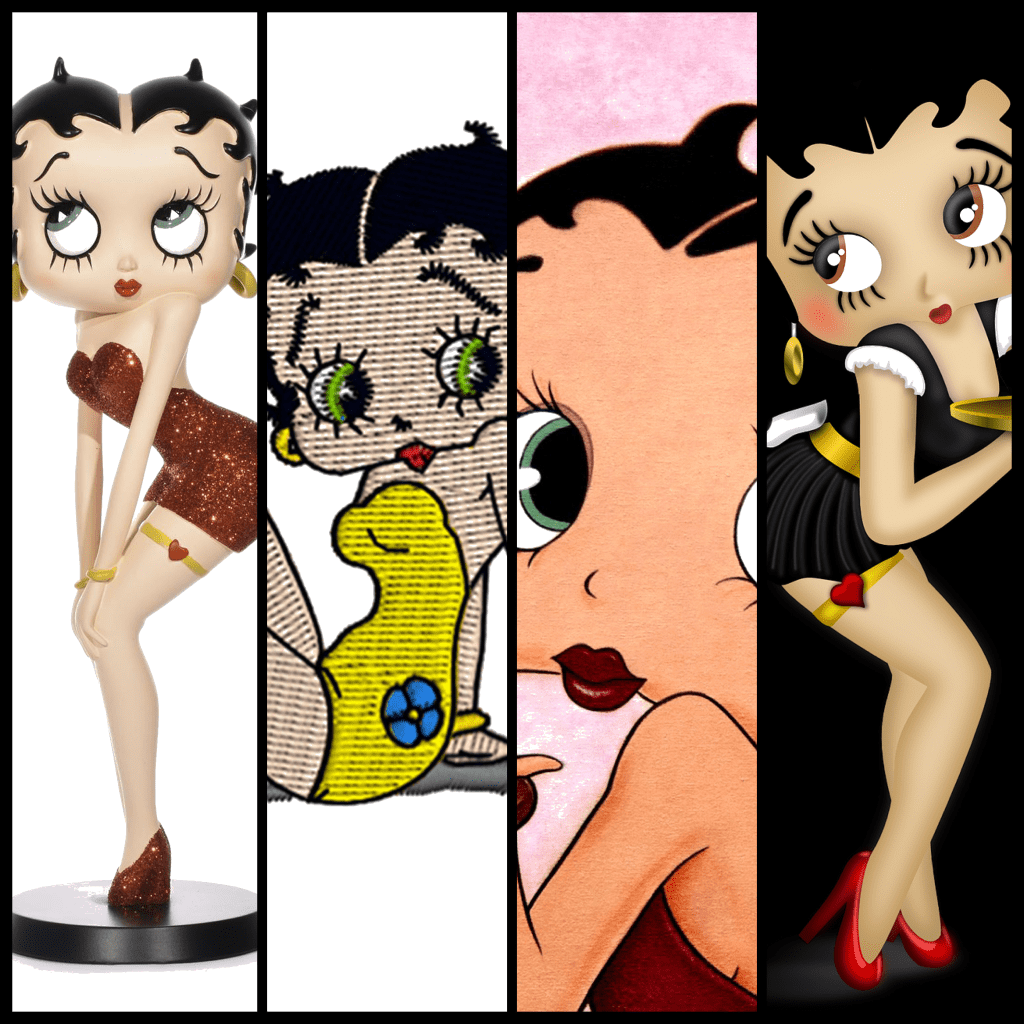

Helen Kane and the Betty Boop Bombshell

Fast-forward to 1928, when Helen Kane, a white singer with a babyish voice and a knack for flirty tunes, dropped “I Wanna Be Loved by You.” The song’s “Boop-Oop-a-Doop” hook was an instant hit, and Kane leaned into it, claiming it as her own. Her cutesy persona inspired Fleischer Studios to create Betty Boop in 1930, a cartoon flapper who became a global sensation with her big eyes, short skirts, and that oh-so-familiar scat.

But here’s where it gets juicy. In 1932, Kane sued Fleischer Studios and Paramount Pictures, crying foul that they’d stolen her likeness for Betty Boop. The courtroom drama took a wild turn when a 1928 film of Baby Esther surfaced, proving she was scat-singing “Boop-Oop-a-Doop” long before Kane. Animator Shamus Culhane, in his 1986 book Talking Animals and Other People, spilled the tea: under cross-examination, Kane admitted she’d borrowed the phrase from “an obscure Black singer” named Baby Esther.

Richard Fleischer, son of Betty’s creator Max Fleischer, backed this up in his 2005 book Out of the Inkwell, calling the film the smoking gun that exposed Kane’s inspiration.

The Erasure and Rediscovery of Baby Esther

The revelation about Baby Esther wasn’t just a courtroom win—it was a stark reminder of how Black artists were often erased from the spotlight. Esther’s contributions were overshadowed as Helen Kane and Betty Boop took center stage, reaping fame and fortune. For decades, Esther’s name faded into the margins of history, her story buried under the glitz of Hollywood and animation.

But the tide is turning. In 2021, stars like Taraji P. Henson and Big Freedia shouted out Baby Esther, celebrating her as a trailblazer who shaped jazz, scat, and even pop culture’s favorite cartoon flapper. Fans and historians are digging into her legacy, sharing posts that hail her as a forgotten icon. Esther’s story isn’t just about a catchy phrase—it’s about reclaiming the narrative for Black women who’ve been overlooked for too long.

Why We’re Still Booping Today

So, next time you see Betty Boop’s saucy wink or hear that “Boop-Oop-a-Doop,” think of Baby Esther, the kid from Harlem who sang her heart out and sparked a cultural phenomenon. Her story reminds us that behind every iconic moment, there’s often an unsung hero waiting for their due. The jazz clubs of the 1920s may be gone, but Esther’s voice echoes on—in every scat riff, every Betty Boop cartoon, and every artist who dares to create something new.

Let’s keep booping, grooving, and giving props to the real stars like Esther Jones. Who’s ready to rewrite history with a little scat and a lot of soul?

Contact Sylvie DeCristo for the Too Cute for Words Movie Treatment and Investment Opportunity at contact@innervision.pictures

Longline

In the glittering 1920s, child prodigy Little Esther Lee Jones ignites the world with her enchanting Divine Feminine grace, sultry scat-singing, and timeless Charleston flair—until a shadowy conspiracy silences her brilliance forever. Decades later, the very architects of her erasure unwittingly breathe life into her legacy as the iconic Betty Boop, whose spectral presence now haunts a relentless modern historian-singer. Racing against a chilling past, she unravels the dark 1920s plot, where every clue teeters on the edge of revelation and ruin.

References

1. Culhane, Shamus. Talking Animals and Other People. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1986.

2. Fleischer, Richard. Out of the Inkwell: Max Fleischer and the Animation Revolution. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2005.

3. Archival records of Shuffle Along and Gertrude Saunders’ performances, sourced from Broadway histories.